What is Bad Character Evidence?

As a suspect or defendant, you may have heard the term ‘bad character evidence’ discussed between your legal representative and or with you. In a criminal case, bad character is a term used to describe a person who has a history of misconduct other than what they are being investigated or prosecuted for. This misconduct does not have to be a previous criminal conviction.

Bad character does not just apply to a defendant, there can also be non-defendant bad character which could relate to the complainant of a crime, or witnesses in proceedings.

Legal definition of bad character

Section 98 of the Criminal Justice Act 2003 defines bad character as evidence of, or a disposition towards misconduct, other than evidence which has to do with the alleged facts of the offence with which the defendant is charged, or is evidence of misconduct in connection with the investigation or prosecution of that offence.

Misconduct is further defined by the Criminal Justice Act as the commission of an offence or other reprehensible behaviour. This may include previous convictions, and/or behaviour which may amount to a criminal offence but was never investigated or prosecuted. Reprehensible behaviour does not have any particular legal definition and is therefore considered on a case-by-case basis, considering the particular circumstances of the case and the alleged reprehensible behaviour.

Will the jury hear about my previous convictions?

The jury cannot just be told about a defendant’s previous convictions, for this information to be presented to the jury the Crown Prosecution Service would have to make a bad character application, prior to trial.

Bad character evidence is only allowed to be introduced in criminal proceedings if one or more of the following gateways are met:

- all parties to the proceedings agree to the evidence being admissible, - this means that both the prosecution and the defence agree for the bad character evidence to be disclosed.

- the bad character evidence is adduced by the defendant himself or is given in answer to a question asked by him in cross-examination and intended to elicit it – this usually arises where the defendant themselves discloses their previous convictions in open court during their trial so that the jury hear it directly from them.

- it is important explanatory evidence – it is important for the jury to hear the details of a defendant’s bad character to ensure they understand a particular aspect of the current case against the defendant.

- it is relevant to an important matter in issue between the defendant and the prosecution. This can include circumstances whereby the defendant has committed offences of the same kind before, or where they have committed offences which show they have a history of being untruthful.

- it has substantial probative value in relation to an important matter in issue between the defendant and a co-defendant.

- it is evidence to correct a false impression given by the defendant. This can include where in an interview under caution or when giving evidence in the witness box, they give information which is proved to be untrue such as a defendant who may suggest they are an honest person, but then have a conviction for theft.

- the defendant has made an attack on another person’s character. If a defendant attacks another person’s character, where they in fact themselves are not of good character, this could lead to the prosecution being allowed to explain this to the jury.

- Even is one of the above gateways are met, there are complex legal arguments which defence lawyers can advance to stop bad character being disclosed to a court during a trial. Responding correctly to an application for the bad character of a defendant to be admitted is crucial, and often requires detailed responses which deal with legal technicalities.

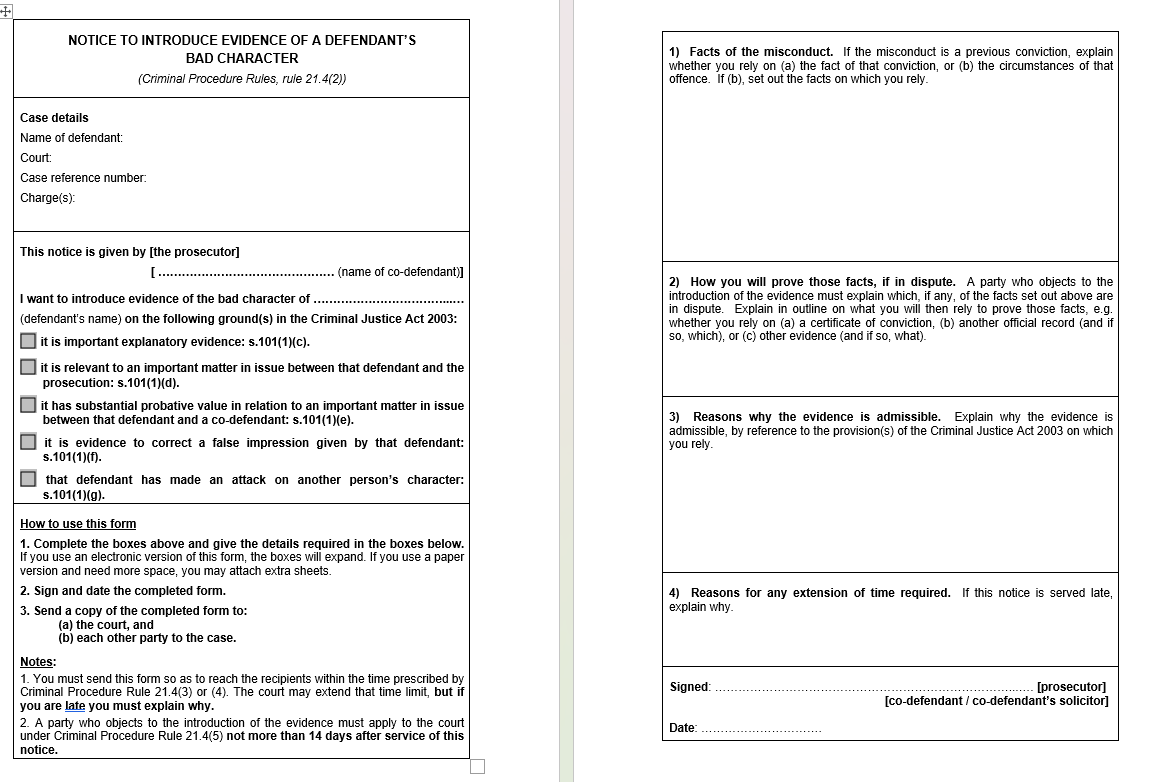

What should a bad character application include?

A bad character application is a two page document which requires the lawyer completing the form to confirm firstly the details of the case and the ground on which they are relying on to introduce the bad character evidence. They must then go on to complete questions 1-3 which would include any legal argument, or law being relied on.

Once the application is served on the court and other party a response will be drafted and submitted by the defendant's legal team. Where it is not agreed a hearing at court will take place and it will be for the judge to decide, upon hearing legal arguments from both sides as to whether the bad character evidence is allowed to be disclosed to the jury during the trial.

What will happen if bad character evidence is allowed?

If the judge allows the prosecution to introduce the bad character evidence of a defendant then defence lawyers should take all possible steps to ensure that this is delivered to the jury in the least harmful way possible. This may include the defendant admitting the bad character evidence within their evidence and beating the prosecution to it. This is a tactical decision that should only be made with the advice of an experienced legal team.

Non-Defendant Bad Character

During criminal proceedings it may become apparent that a witness or the complainant themselves has a history of misconduct which may or may not include previous criminal convictions. In this instance the defence can apply to introduce the bad character of the witness or complainant which may assist the defendant and undermine the case against them. To do this a similar form to that above is completed and served on all parties.

What about good character?

Evidence of character can also relate to good character. This would apply in circumstances where a defendant has no previous convictions and can be helpful to show two things during a criminal trial:

1. that the defendant is less likely to have committed this offence because they are a person of good character and;

2. a defendant with no convictions is additionally entitled to a good character direction as to their credibility where, before trial, they asserted their innocence at a police station or during their evidence given at trial on the witness stand.

The direction for good character is referred to as a Vye direction, the name comes from a court of appeal case R v Vye [1993]. It is crucial your legal team ensure that this direction is given to the jury, where the circumstances apply.

How can we help you?

Avoiding bad character being admitted during criminal proceedings is essential and it is therefore very important your legal team understand and can apply the law surrounding this area and can prepare strong legal arguments to protect you from this.

It is also important that the bad character of witnesses or the complainant is explored and dealt with correctly, this in turn has the potential to impact an accused’s case dramatically.

At Eventum Legal our team have been challenging bad character applications in the Magistrates and Crown Courts for many years and understand exactly how to deal with issues of bad character evidence that can arise during criminal proceedings, particularly proceedings relating to sexual offences.

If you would like to discuss any issues that may arise or have arisen in your case, and you are concerned about how this may affect your trial then we can hold a free initial case conference with you to discuss our approach and how we can help. You can complete our online enquiry form following which we will contact you, or you can call and speak to a lawyer now on 0161 706 0602.

We Can Help With